A lovely American couple moved into the region this past year and they include me in their mailing list of updates home to family and friends. I love reading them, not just because they are funny and honest, but because it reminds me of what it was like my first year here as well. Everything was exciting, fresh, a new discovery. If I go through my photo album from that time there are exponentially more images of me doing mid-air jump shots in front of random Japanese tourist sites and flashing two-fingered peace signs like Winston Churchill was in town. If you flip forward in my album you’ll notice that pictures these days rarely have me in them, cause I spend most of my time trying to digitally immortalize Noah rather than keep an enduring record of my own stark aging process. Times change.

Additionally, my friend’s newsletter well explains how frustrating it can be to live in an existence where you can’t read, write or speak the local language. At times the politeness of Japanese culture doesn’t help any either. It’s actually been easier for me get things done in more abrupt cultures, like in parts of remote Russia, where they so desperately want to get rid of you that after you’ve pointed at and paid for the thing you want in the store window they turn away unsmiling and pretend that you no longer exist. But here, even though there is a mutual understanding that neither party will be able to verbally understand each other, the clerk or cashier will inevitably ask you all the same, beautifully complex respectful phrases they’ve been taught to say to everyone. Would you like a bag? Do you need a straw, chopsticks, a spoon? You just gave me 1000 yen. Do you have a point card? Your change is 22 yen. Are you sure you don’t have a point card? Do you want one? Here’s a coupon you can’t read and will never use. Thanks for your business. With all that extra linguistic dressing the most basic of tasks can feel overdrawn and more confusing than it ought to be. It took a while to get the hang of buying groceries, but I’m happy to say that I no longer break down in tears when I try to buy eggs or milk at the market. And just the other day, finally, after 4 years of hearing the same announcement played a hundred plus times over the loudspeaker at the local all night supermarket, I registered what it was saying. You must be 20 years old to buy alcohol and tobacco.

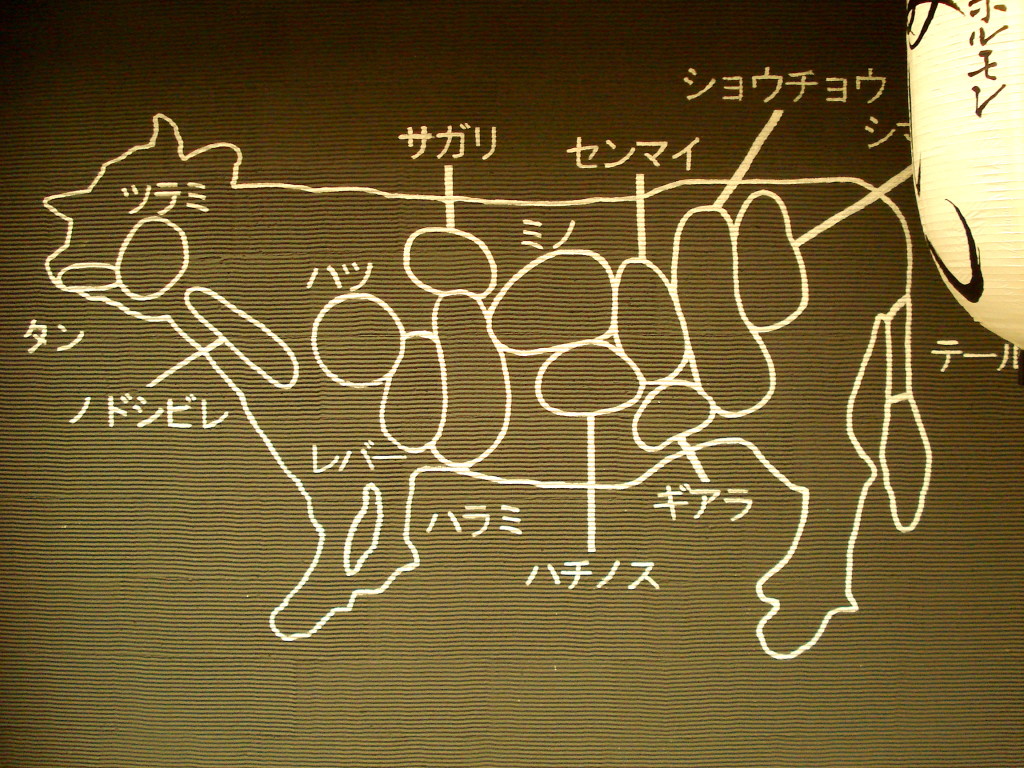

Now if you think of how utterly simple selecting and paying for food is, but how enormous a task it can become when you are essentially illiterate, you can appreciate how much more difficult everything else can end up being. Buying stamps, taking a bus, doing anything at the bank, ordering food at a restaurant with no picture menu, trying to get rid of Japanese speaking Mormons who turn up on your doorstep, telling a hair stylist to give you a trim, going to the doctor, going to the doctor with your sick son, going to the doctor again with your sick son after you went the first time and things didn’t get better, breaking a sweat trying to write your address, filling out your kids daycare sheet every morning, answering the phone at your desk, trying to fix your faulty internet, visiting the dentist or gynaecologist or immigration office (and no the immigration officer does not speak English for some reason), being pulled over by the cops, trying to get rid of the NHK cable guy trying to collect money for cable you don’t have, getting a driver’s licence, having your garbage rejected and not understanding why until someone smartly takes a magic marker and circles the forbidden item through the plastic bag, getting a cell phone (this one is the worst because not even a native speaker can understand the crazy phone plans), getting lost anywhere with or without a map, giving condolences to your neighbour after her husband dies, trying to differentiate between detergent, softener and bleach.

It goes on, and really it never stops even as you start to get a grip on the basic language skills, because inevitably the longer you stay, the more complex the problems become, and you end back at square one thinking how great you thought your Japanese was but then realizing actually how shitty it is. Yes, this was exactly where I found myself last week when Noah got sick and refused to eat anything for 3 days. The doctor said it was a throat infection, prescribed me all sorts of mystery medications that I would administer faithfully but saw little change. One night in lieu of taking him to the emergency room in fear that I couldn’t even tell the cabbie where to go, I called my sister on the other side of the world. She said…luke warm baths, cold compresses, lots of fluids…all simple reassuring things that helped me get a grip in that moment. It was so good to hear it in English. The next morning I stood at the gate of Noah’s daycare trying to ask if he could attend that day because his fever wasn’t so high. I repeated 3 times over in the worst possible broken Japanese “Is it ok? I can stay for a bit to watch him and make sure he’s fine.” No one understood me. Three times over and then I broke, bowed my head, put my hand over my eyes and just cried. Well, that got their attention. At least tears are universally understood. The one worker who always looks at me like I’m the most novice of mothers and that I have a lot to learn was the one who put her hand on my back asking me over and over “What’s wrong? What’s wrong?”

Ahhhh. What’s wrong? That was a good question. The problem was and is that even if I could speak perfect Japanese, there is no way I could tell her, because what’s wrong really cannot be verbalized in that sort of moment. It’s a feeling more than anything else, one that boils up to a point of uncontainable pressure, where your mind sort of short circuits as it searches for any possible word that will get the message through, but you can’t find it because you don’t know it and you feel utterly alone and helpless and frustrated because nothing, absolutely nothing is helping you be you and do what you would do in that moment if that moment was happening someplace else. Yes, it is the feeling you get when you lose yourself to a language. That’s it exactly. So instead of trying to say any of that, I told her “I’m not very good at Japanese.” I think she understood.

Some of us foreigners here like to throw around the term ‘expat’, trying to disguise the fact that what we really are, are temporary immigrants. Immigrant has always seemed like such a dirty word to us North Americans. It implies balconies full of garbage, smelly food, strange ways of dressing, clothing hanging any which way for days on end on the clothes line and sometimes left out when its raining, being late for everything, a lack of education or class or politeness and an all around inability to get with the program. I don’t know about you or anyone else, but that description pretty much sums up my Japanese life in a nutshell. Ask anyone in my neighbourhood where the foreigners live and they could tell you by the way we park our car or leave Noah’s toys lying around the back of our building. Or better still, just stand quietly for a minute or two and I am sure you will hear our loud western voices carrying through our paper thin walls amidst the other silent houses. Somehow my bike repair guy successfully found our apartment and dropped off my bike only with the knowledge that I lived somewhere over the hill from his shop. It’s a big hill. It’s almost a 20 minute walk.

All this is to say, now that I’ve experienced just exactly what it’s like to live the immigrant lifestyle, with all the language and culture barriers that come with it, I don’t think I could ever tolerate another person saying something as stupid as “You’re in a America now, act American!” It will also take all of my willpower not to throw something hard and heavy at that person’s head. You’d never hear a Japanese person say “You need to start acting Japanese.” In fact, I’m sure they don’t even think it’s possible. Their mindset is that someone who is not Japanese is going to have a very difficult time naturally acting like one, so why expect it of them? They are thrilled when we try and succeed, but they set the bar very low for foreigners in this department, which might explain why I still have so many good Japanese friends despite all the cultural blunders i’ve made. Some foreigners take a personal affront to this though, especially those who have lived here for a long period of time or who have married a local. The phrase “You will never be one of them” is often thrown around negatively, but the idea doesn’t bother me. Of course I’ll never be one of them. How can I be? I’m Canadian.

So here is where I would like to mention that there is no way in hell that I could be as happy as I am here in Japan without the amazing and absolutely selfless Japanese friends I have made who time and time again come to my rescue. To my neighbour who is usually coerced into explaining all of Noah’s daycare tasks and requirements, thank you. To my colleagues who not only helped me set up my life here, but still patiently remind me to this day of reminders that are clearly written in front of my face on the announcement board, thank you. To my dearest of dear friends who came to ultrasound sessions, interpreted at Noah’s birth, sat through emotional talks with my pastor, helped me fill out mountains of paperwork for every possible government office imaginable, and who waited on hold with tech support for more times than I can remember, thank you, thank you, thank you. I’m sorry, but I don’t think there is any way I could ever repay you for everything you’ve done for me. Even so, thank you.

Story and photos by Martine Duprey